Meet Leah Simon: Preservation Intern

Meet Leah Simon: BAVC Media Preservation Intern

Working with BAVC Media as a preservation intern was a real treat. Coming to video preservation and digitization as a graduate student studying Folklore and archival theory, I had never worked with tape collections before BAVC Media.

Not only was I able to apprentice with knowledgeable mentors like Morgan Morel, trained at the University of Michigan’s Information Studies Program, or Anne Smatla who graduated from the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation, but through their mentorship, I was given the training to work with a wide range of tape material that I had never encountered before. These formats spanned from U-Matic, ½” Open Reel EIAJ, 1” Open Reel SMPTE Type C, betacam, and VHS.

Through hands-on work with collections from NYU Bobst Library, Walt Disney Archives, and the Walker Art Center of Minneapolis, I was able to grasp a more nuanced understanding of preservation protocol in a non-profit space. One of the best parts of the job was working with older, more obsolescent tape technologies: working with RTI TapeChek VT-3100, adjusting time based correctors to set video signal levels, and engaging with any old-school technologies housed with the BAVC Media preservation team. In my earlier weeks at BAVC Media, I shadowed Anne as she worked on digitizing over 2,300 VHS and U-Matic tapes from the Walt Disney Archives.

Day to day, I helped pack, clean, and sort ½ inch tape format, VHS, and U-Matic collections. In the afternoons, I would work in our tape closet with BAVC Media’s cleaning decks where I would pack and inspect new collections. During these sessions I encountered tapes stored “tails out,” sticky shed, and tape expansion all for the first time– sources of grief for any archivist handling open-reel tape materials. As a response, I was able to quickly develop my own procedure for getting tails out tapes back onto their original reels (packing tapes three times) or baked at the proper temperatures to reduce sticky shed.

I was taught how to distinguish between: inherent tape damage and tape damage from generational wear or sync errors; learning more about dropouts, what they are, and how they occur (when dirt clogs or obstructs the magnetic head’s contact with the tape); tape errors that are momentary errors as opposed to sustained or continuous errors; and the different kinds of damage or errors specific to each tape format that we work with at BAVC Media.

All of the tape errors that I encountered were cross-listed in the AV Artifact Atlas (AVAA), a guide that I spent time studying during my preservation work. The Atlas, created in partnership with New York University’s Digital Library Technology Services and the Stanford Media Preservation Lab, is an open-source guide used to identify common technical issues and anomalies that impact audio and video signals. These include: tape crease, chroma banding, dropouts, cross color flickering, image echo, edge damage, tape warping, and severe popped strands. In addition to mapping and detecting various kinds of tape damage, I spent time with inspection notes and learned how to tailor each set of notes to the concomitant formats I was tasked with evaluating. While I know I have only just grazed the surface, I look forward to learning more about video preservation from the AVAA and the other teaching materials that BAVC Media provided me with. I look forward to future hands-on experience ahead as I continue to familiarize myself with preservation and archival training with tape, print, and film material.

Professional Tool Tips and Managing Intake

Professional Tool Tips and Managing Intake

By the end of my time at BAVC Media, I fashioned a set of “professional tool tips” to drive workflow enhancement. These tips aim to address prescient questions that might arise as one practices tape inspection, packing, or cleaning for the first time. In order to set interactive reminders, I fashioned notes within Salesforce, the cloud-based software company used by BAVC Media for the inventory of client collections and tracking conversion progress. My tips broke down various issues: from what to do when encountering mold; breaking down what is ‘normal’ in coloration or texture of tape; what may indicate wear or sticky shed; and tips on discarding the recording tab on VHS or U-Matic tape formats. These tips ultimately stressed what kinds of details an archivist conducting intake should look out for and notate in order to offset liability or risk for the preservation group capturing the collections. One tool tip broke down what kinds of odor to look for, describing what smells to anticipate while evaluating tape condition, i.e. the smell of “crayons” “wax” or “stinky socks” indicates signs of sticky shed.

Finally, under the mentorship of all of the preservation team at BAVC Media, Morgan Morel and Anne Smalta, and Jackie Jay, I was able to intuitively memorize what running times matched given formats, saving the work of having to look up this information online or to ask my supervisors. To drive workflow enhancement I created a tool tip that detailed each length of tape (running time) description:

• VHS Ex: “T-120” (tape runs 120 min)

• U-matic Ex: KCA60 (tape runs 60 min)

• ½” Open-Reel Video: 5” reels run 30 min

• ½” Open-Reel Video: 7” reels run 60 min

Overall, these tips are geared to respond to questions as they arise to a novice intake archivist of tape material like myself. I hope these notes will help future interns or novice archivists in this field, those who may be coming to tape format and intaking client collections for the first time. With a good amount of weekly exposure to playback equipment, intake procedure, tape cleaning, as well as capture and digitization, I look forward to building more familiarity with these practices and hope to work for another nonprofit preservation lab or archive in the future.

Preserving my parent’s wedding video

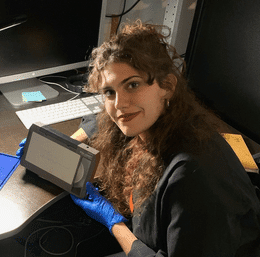

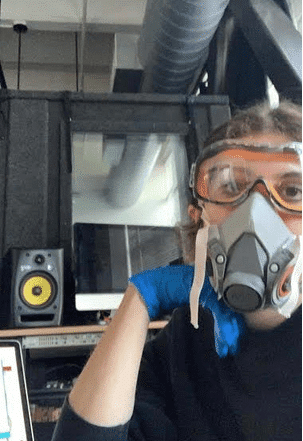

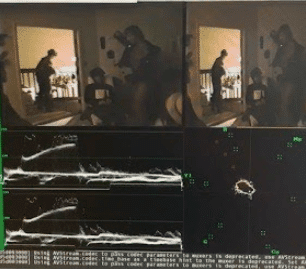

[Images 1, 2 : shots of me adjusting light, coloration, and chroma during playback capture]

Eventually as my post at BAVC Media was coming to a close, I wanted to apply the skills that I had learned while working with other collections. I was ready, in other words, to handle a collection from start to finish (meta data inventory and cleaning, to digitization, capture, transcode notes, quality control). After a visit home to coastal Virginia, I retrieved a box of VHS tapes that were experiencing mild warping and edge damage. In this box, I found my parents 1992 VHS wedding tape that was in precarious condition of being lost to time with no digital copy. In archive circles, magnetic tape is not considered a secure, long-term storage solution for archival material. As the Video Preservation Handbook written by Jim Wheeler offers, “The archivist is therefore faced with the problems of maintaining obsolete equipment and having to migrate (copy or transfer) material to a newer tape format or a different type of medium.” First steps in my process of digitization: I notated all manufacturing details of the tape and I conducted a formal inspection of the tape’s condition. Next, spanning two hours, I was able to capture this material in digital format, adjusting color, luma, sound, and notating all tape errors. After capture, I had produced three file copies and had a collection of intake notes. My three file copies of the archival material included: 1- the access file at the bottom quality (am.mp4); 2- the mezzanine file (pm.mov) or production master, de-interlaced; and 3- the preservation master or raw file as it came after capture. Portions of the tape had to be run twice in order to capture the Liner and Hi-Fi audio tracks. This offered a teaching moment between myself and my mentors at BAVC Media. I learned that different recording hardware captures sound differently, where one of the camcorders being used had recorded only linear while the other used HiFi. This meant that we had to switch the playback deck settings throughout various sections to properly capture the audio.

Participating as a panelist for BAVC Media’s Preservation Access Program 2019

Participating as a panelist for BAVC Media’s Preservation Access Program 2019

Perhaps the most rewarding experience as a preservation intern at BAVC Media and an archivist in training, I was offered the opportunity to participate in the Spring 2019 review panel for BAVC Media’s Preservation Access Program (PAP), an annual grant competition sponsored by the support of the National Endowment for the Arts and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. One aspect that drew me to want to work with BAVC Media was this program, where the preservation team offers up to fifty percent discounted pricing on all preservation services for individual artists and small-to-medium-sized cultural heritage organizations. Each year BAVC Media preservation receives applicants from local museums, libraries, historical societies, visual, performing, and cultural arts organizations, and grassroot nonprofits– often making it difficult for panelists to choose which collections to sponsor over others. This year our panel was made up of a range of archivists, editors, and members of the larger film, video maker, and preservation community of the extended bay area. Participants for review in the program included: GLBT (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender) Historical Society, San Francisco Moma, Third World Newsreel, Oregon Historical Society, and Chicago Film Archives amongst others. Each round of applicants is reviewed by the PAP panel which determines whose collections will be given the Mellon grant for transfer to digital format. This funding helps to preserve approximately 350 tapes and their content, prioritizing ½ “ open reel video recordings, individual artists, small organizations, collections that have an access/distribution plan, and smaller collections.

As spring panelists, we were instructed to vote for our favorite collections based off of those we felt were at risk of deterioration and obsolescence, had strong cultural significance, and whose applicants expressed interest in providing public access or creating new work with the material. Some of my favorite applicants included broadcast footage from the El Salvador Civil War, personal footage from pre- New Orleans Hurricane Katrina, and 1990s never before transferred Oakland footage of LGBT activism targeting the AIDS pandemic in northern California. I very much look forward to participating in these kinds of panels and discussions on making historical material accessible and public in the future. I also look forward to learning more about the role of archivists and preservation in these spaces more broadly. I am grateful to the preservation and transfer team at BAVC Media for all that they have taught me, and I look forward to what is ahead!

Participating as a panelist for BAVC Media’s Preservation Access Program 2019

Participating as a panelist for BAVC Media’s Preservation Access Program 2019